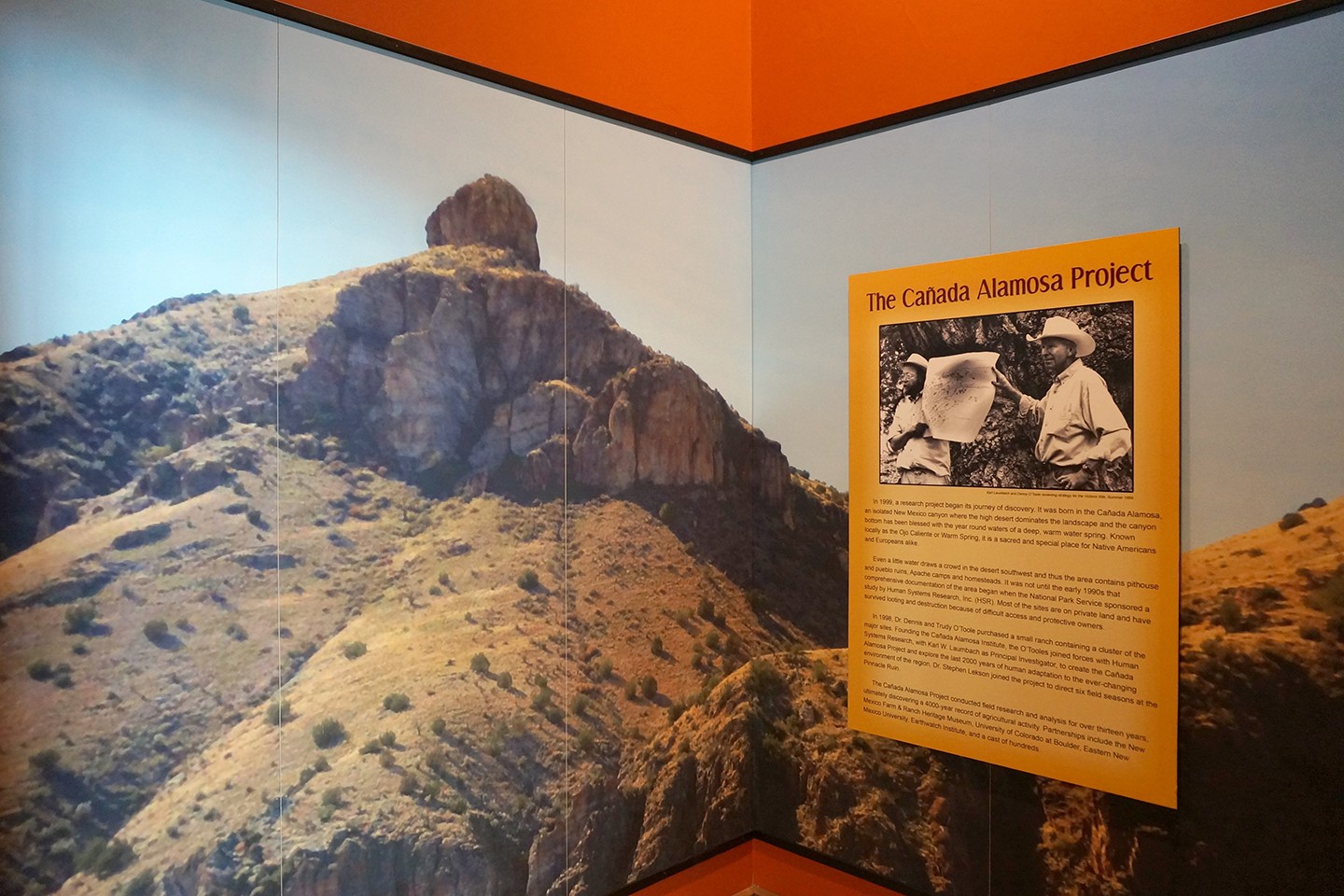

In 1999, a research project began its journey of discovery. It was born in the Cañada Alamosa, an isolated New Mexico canyon where the high desert dominates the landscape and the canyon bottom has been blessed with the year round waters of a deep, warm water spring. Known locally as the Ojo Caliente or Warm Spring, it is a sacred and special place for Native Americans and Europeans alike.

Even a little water draws a crowd in the desert southwest and thus the area contains pithouse and pueblo ruins, Apache camps and homesteads. It was not until the early 1990s that comprehensive documentation of the area began when the National Park Service sponsored a study by Human Systems Research, Inc. (HSR). Most of the sites are on private land and have survived looting and destruction because of difficult access and protective owners.

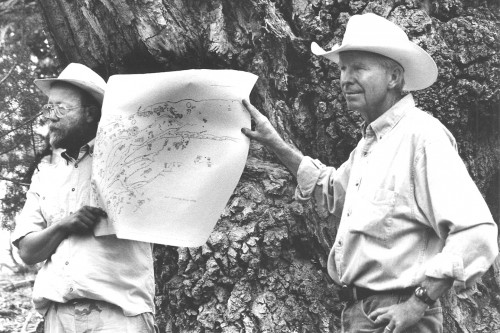

In 1998, Dr. Dennis and Trudy O’Toole purchased a small ranch containing a cluster of the major sites. Founding the Cañada Alamosa Institute, the O’Tooles joined forces with Human Systems Research, with Karl W. Laumbach as Principal Investigator, to create the Cañada Alamosa Project and explore the last 2000 years of human adaptation to the ever-changing environment of the region. Dr. Stephen Lekson joined the project to direct six field seasons at the Pinnacle Ruin.

The Cañada Alamosa Project conducted field research and analysis for over thirteen years, ultimately discovering a 4000-year record of agricultural activity. Partnerships include the New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum, University of Colorado at Boulder, Eastern New Mexico University, Earthwatch Institute, New Mexico State University, University of New Mexico, Maxwell Museum and a cast of hundreds.

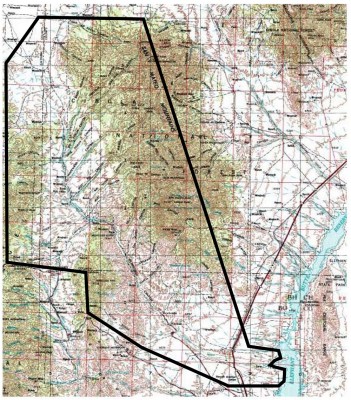

The Project Area

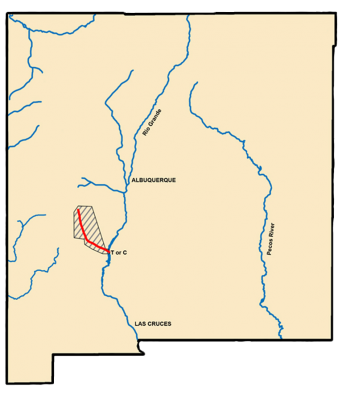

The Rio Alamosa watershed encompasses 728 square miles from its headwaters to its confluence with the Rio Grande. Bounded on the east by the San Mateo Mountains and to the south and east by the foothills and mountains of the Black Range, the Alamosa is the northernmost drainage in this range, each stream running east towards the Rio Grande, sometimes on the surface and other times dropping underground. From north to south the creeks are the Alamosa, Cuchillo Negro, Palomas, Seco, Las Animas, Percha, Trujillo, Tierra Blanca, and Berrenda.

As the drainages flow from west to east, each passes through the representative zones of a Southwestern landscape, marked first by ponderosa, then by pinyon and juniper, by grasslands, by mesquite and creosote bush, and finally to the riparian bottoms of the Rio Grande. The geology of the area was determined by vulcanism during the Tertiary Period in the form of rhyolitic and andesitic intrusions. Most of the exposed geology consists of andesite-latite flows and dykes. Occasionally, siltstone and sandstone sediments are exposed between the flows.

The center of the project area lies under the shadow of Montoya Butte, once a Native American shrine. It is an oasis of farmable land and a spring-fed creek that made this location a center of human activity. Four sites in this desert oasis have been systematically tested over the course of 13 years.

Life Giving Waters

The Ojo Caliente, or Warm Spring, rises from a 1500-foot-deep aquifer to feed the Rio Alamosa in a constant, abundant flow even in drought years. Measured at an incredible 2000 gallons per minute this tepid water flows down a small side canyon and drains into the Cañada Alamosa. It moves between the high canyon walls of the Monticello Box, and then irrigates the historic farms in the canyon. For the first three miles, the canyon narrows before opening at the Monticello Box Ranch. At this point in the canyon, subsurface water from the eastern slope of the canyon creates a cienega that was once known as La Cienega de Victorio after the Apache leader. It is here that Pueblo farmers built the series of villages that the Cañada Alamosa Project is investigating.

The Environment

Three major biotic zones meet at the core of the Cañada Alamosa study area. From the mouth of the Rio Grande to just west of the community of Monticello, the Chihuahuan Desert Zone is dominated by mesquite in the sandy areas and creosote on the mesa tops that were graveled by the ancestral Rio Grande. Desert grasses, forbs (non-grass plants), and other shrubs complete the scene. The highest elevations in the San Mateo and Wahoo Ranges are in the rugged Upland Zone, forested with ponderosa pine, aspen, and spruce. The lower elevations are in the Grassland Zone, which is occasionally dotted with juniper. The center of the area, where these three zones meet is an ecotone (a community of mixed vegetation formed by the overlapping of adjoining communities). Locating a village on the ecotone allowed access to multiple resource zones for prehistoric and historic inhabitants, all within a day’s walk.

The area averages annual precipitation of 15-20 inches in the upper elevations to 11 inches in the lower areas. Most of the precipitation comes in the form of summer rains, which fall, typically, between early July and late September. Daily temperatures range from the upper 30s to the mid-80s in late April and May and from the low 30s to the mid-70s in late October. Humidity is normally very low, and the sun shines almost every day. The spring months can be windy.

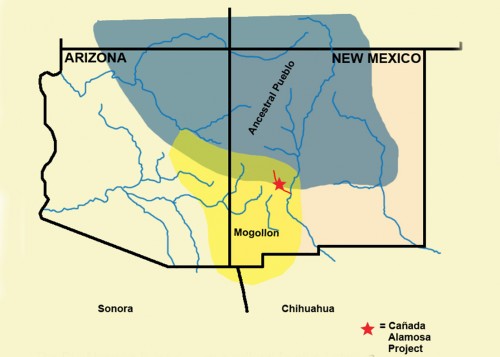

Life on a Frontier

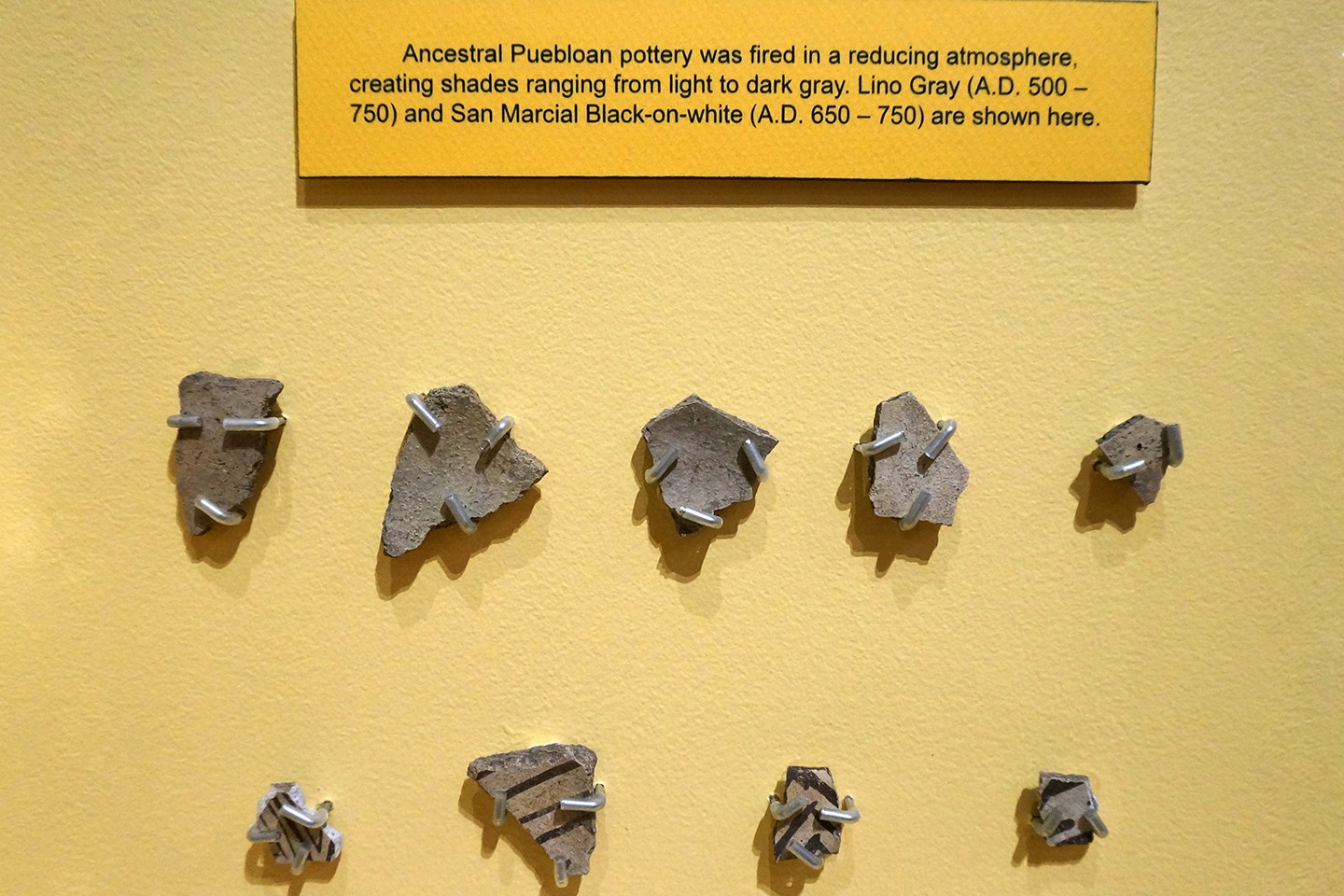

Archaeological frontiers are the outer limits of contact and exchange between culture areas. Archaeological boundaries are the defined edges of specific culture areas and are based on the extent of their artifacts and architecture specific to a particular culture area. Based on the diverse types of ceramics and architecture found on the archaeological sites, the Cañada Alamosa has long been a cultural frontier. To the south are sites that contain Mogollon-Mimbres architecture and ceramics. To the north are villages of linear room blocks and associated pit structures that contain assemblages of the Ancestral Pueblo ceramic tradition. The sites found in the Cañada Alamosa contain elements of both and there is clear evidence of cyclic expansion and contraction from these adjacent Pueblo worlds.

The archaeological evidence indicates the presence of small communities, perhaps extended families or clans, trying to survive as horticulturalists and/or hunter/gatherers in a harsh environment. In good times, population swelled, in others, adverse environmental conditions limited or prevented life in the canyon, even with permanent water in the canyon bottom. These periods of depopulation may have served to provide the local environment time for rejuvenation. And then, the people would return.

Over time, the depopulation and subsequent repopulation of the area made it a region of refuge or of new opportunity from the epicenters of the Mogollon and Ancestral Puebloan worlds. What is also clear is that each group was tied to their central place by trade, kinship and social ties. That this dependence was never completely broken is evidenced by the lack of indigenous development of ceramic or architectural styles.

This website is based on an exhibition at the New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum in Las Cruces, New Mexico (April 4, 2013-May 4, 2014). The sites discussed in this website are on private land and there is no public access.